When a Foreign Censor Claims Constitutional Injury

The Imran Ahmed Injunction, the December 29 Hearing, and the Deeper Constitutional Issues the Media Isn’t Covering

Read, share and comment on the original X post dedicated to this historic development here.

The headlines say a judge has blocked action against Imran Ahmed; what they do not explain is why the government acted in the first place.

In the days since I published “Imran Ahmed, CCDH’s Censorship Architect Pleads the First Amendment”, the story has moved quickly—and predictably. A federal judge has now issued a temporary restraining order, briefly blocking the Trump administration from detaining or removing Ahmed while the court considers his request for broader injunctive relief. A hearing is scheduled for December 29, where the court will decide whether to extend that pause into a preliminary injunction. (View the restraining order here)

Much of the media coverage has treated this development as a vindication. It is not. A TRO is not a ruling on the merits; it is a procedural pause. Courts issue them routinely when timing is tight and allegations are serious. They do not resolve whether the government acted lawfully, wisely, or within its constitutional and statutory authority. What they do is buy time. That is all.

What remains almost entirely absent from mainstream reporting is the deeper question this case presents: whether a foreign national who helped architect and operationalize one of the most aggressive censorship regimes in modern history can credibly recast himself as a free-speech victim—while avoiding scrutiny of the conduct that prompted government action in the first place.

As I laid out in detail in my earlier piece, Ahmed is not being treated as a random dissident. He is the founder of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, the organization behind the Disinformation Dozen campaign—an operation that explicitly named U.S. citizens, branded them and their speech as lethal threats, pressured platforms to remove and demonetize them, and helped justify government-backed suppression of lawful speech during the COVID era. In public statements and parliamentary testimony, Ahmed went further, repeatedly characterizing Americans who questioned vaccine safety or COVID-era policies as murderers, criminals, psychopathic predators who ‘sell death,’ and even likening them to sexual predators in his Parliamentary testimony—language aimed not at debate, but at moral dehumanization. Americans were punished without notice, hearings, or due process. No injunctions were issued on their behalf.

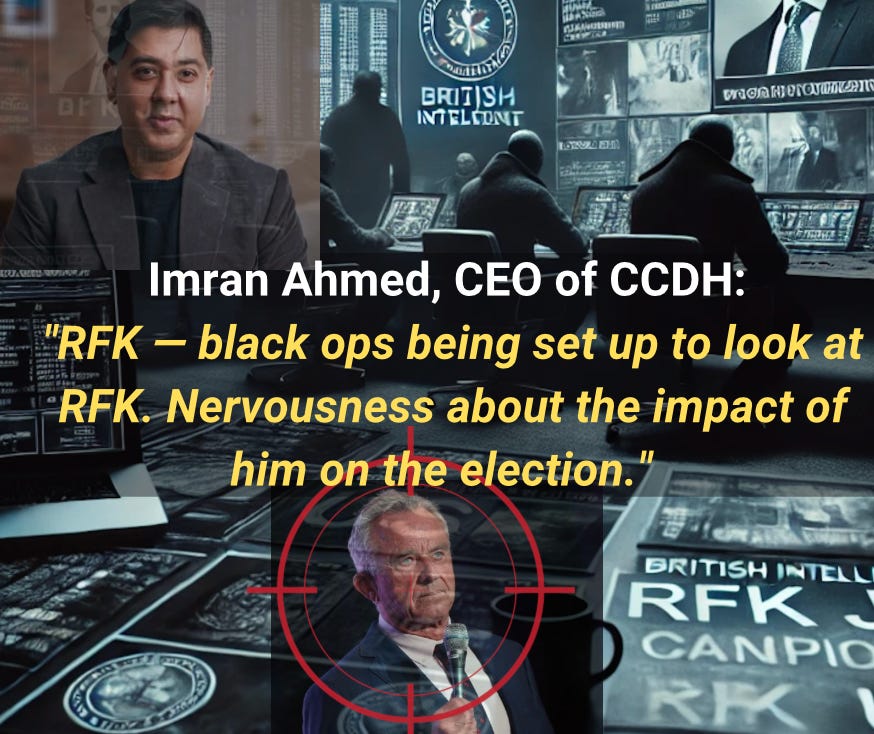

What has also gone largely unreported is the foreign-policy and election-integrity dimension of this case. Internal planning materials and investigative reporting now point to coordination within a broader UK-based political ecosystem, including discussions of “black operations” directed at a named U.S. presidential candidate during an active election cycle. That context matters. Governments are not required to host foreign actors whose activities plausibly implicate foreign influence, coercive pressure campaigns, or election-adjacent operations, particularly when those activities target American speech and democratic processes.

This is why the government’s authority here is being mischaracterized. Immigration and foreign-affairs law have long recognized the executive’s right to deny entry or remove non-citizens whose presence or activities pose potentially serious adverse foreign-policy consequences. That power is not suspended simply because the individual involved invokes the language of civil society or activism—especially when their record shows the deliberate use of moral condemnation and institutional pressure to silence others.

In fact, the State Department has been explicit about the basis for this action. In its December 2025 announcement on combating the “global censorship-industrial complex,” the Department stated that visa restrictions may be imposed on foreign actors who coordinate coercive pressure campaigns against American speech and American companies, citing serious adverse foreign-policy consequences as the governing standard (announcement here).

So as we approach the December 29 hearing, it’s important to be clear about what is—and is not—being decided. The court is not being asked whether censorship was right or wrong in the abstract. It is being asked whether the Constitution must now be wielded as a shield by someone who spent years ensuring it did not protect others; whether the First Amendment is universal, or conditional on one’s proximity to power; and whether the United States retains the sovereign right to draw boundaries when foreign-linked actors engage in coercive, election-adjacent influence campaigns on American soil.

This moment is not about denying anyone their rights. It is about whether those rights apply symmetrically—or only to the architects of censorship once the machinery they built turns back toward them. The answer to that question will matter far beyond this case.

I will continue to follow the December 29 hearing closely and update as this unfolds. The procedural skirmishes may dominate headlines, but the real reckoning lies beneath them.

I think you could be a great lawyer Sayer. You summed it up nicely

I wonder who is paying for Ahmeds representation? He is not a citizen of the US. But, he is a tool of Transnational gangsters assaulting the constitution. Why is he here? Who allowed him in? Who is protecting him?

Persona Non Grata..?