The Blue Brain Effect: Methylene Blue’s Dark Side & What You Should Be Using Instead

Biohackers are turning to methylene blue—but what exactly is this synthetic, petroleum-derived chemical doing to the human body, and at what cost?

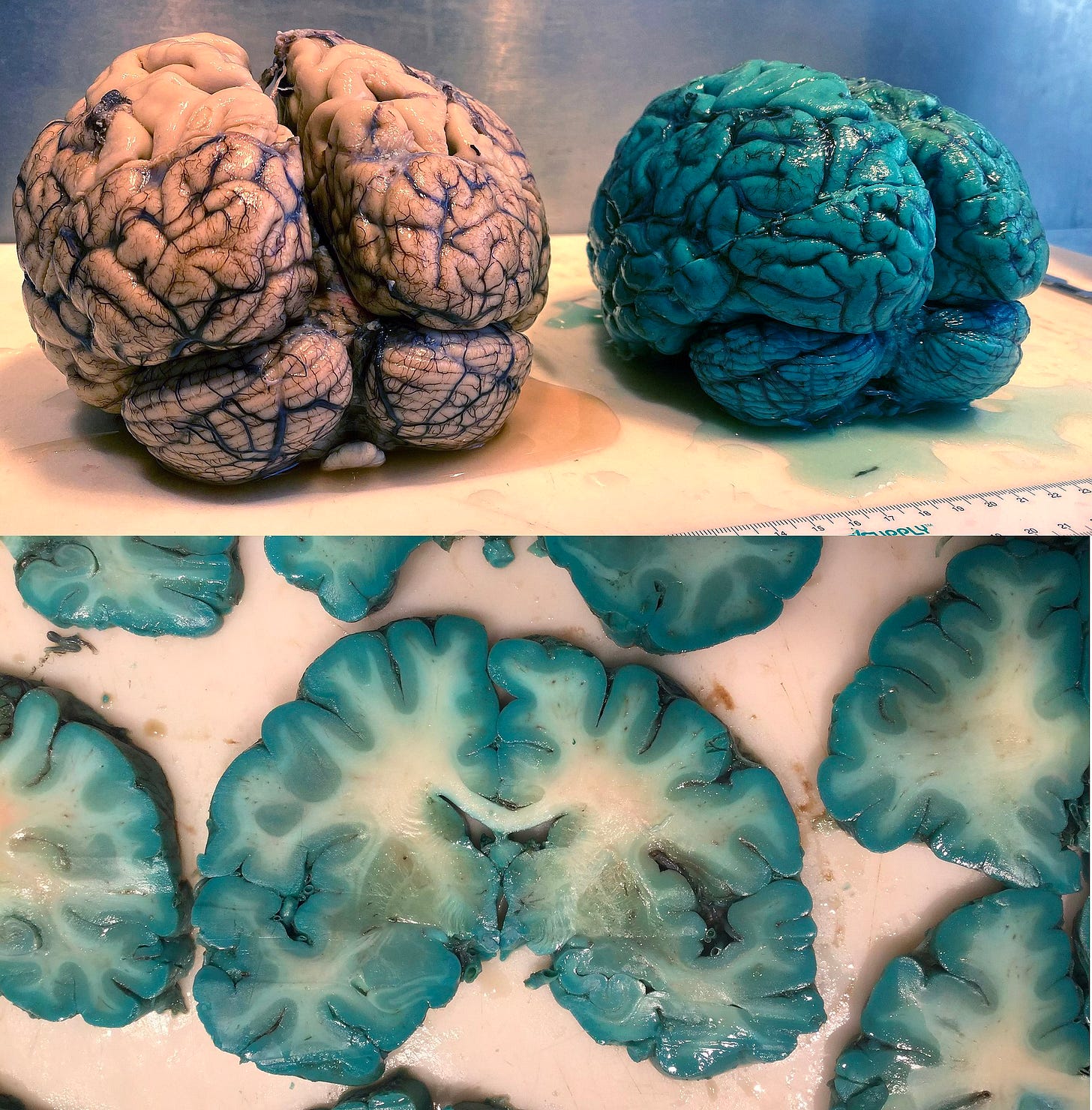

If this is what methylene blue in the brain post-mortem looks like, what is it doing while you're alive?

A recent study published in Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology titled, “Fifty shades of green and blue: autopsy findings after administration of xenobiotics” has brought to light striking findings regarding methylene blue's impact on our internal organs. The research documented cases where systemic administration of methylene blue resulted in a pronounced blue-green discoloration of various organs, notably the brain and heart.

This discoloration is attributed to methylene blue's strong affinity for biological tissues, leading to its accumulation and subsequent staining. The study's observations raise critical questions about the compound's interactions within the human body, especially concerning its potential to cross the blood-brain barrier and the implications of its presence in neural tissues.

While methylene blue has been employed therapeutically within the allopathic medical context for various conditions, these findings underscore the necessity for a deeper understanding of its biodistribution and long-term effects on organ systems, particularly the brain. The visible staining observed post-mortem prompts further investigation into whether such accumulation has functional consequences during a patient's life, emphasizing the need for comprehensive safety evaluations.

Methylene Blue: A Century-Old Medical Staple Under New Scrutiny

In hospitals and medical facilities worldwide, a vibrant blue liquid flows through IV tubes into patients' veins, stains surgical sites, and colors diagnostic tests. This substance is methylene blue (MB)—a synthetic compound that has been used in medicine for over a century. While touted as a treatment for conditions ranging from malaria to circulatory shock, emerging research suggests it's time to reassess our understanding of this widely used substance and approach its use with greater caution.

The Synthetic Origins of a Medical Mainstay

Methylene blue was first synthesized in a laboratory in 1876 as a coal tar derivative. Its molecular structure, composed of heterocyclic rings containing sulfur and nitrogen, is entirely foreign to human biology. Unlike naturally occurring molecules that our bodies have evolved alongside, MB is a xenobiotic, meaning it is foreign to life processes.1

Despite its synthetic nature, methylene blue was rapidly adopted for medical use, starting with malaria treatment in the early 1900s.2 Over time, new applications were discovered—ranging from treating methemoglobinemia to acting as a urinary tract antiseptic, a surgical dye, and even as an experimental nootropic.3 However, its widespread adoption has occurred without long-term safety studies, making its continued use an ongoing human experiment.

The "Less is More" Paradigm: A Call for Caution

The conventional toxicology model assumes that below a certain threshold, substances cause no harm.4 However, modern research has shown that synthetic chemicals can exert biological effects even at infinitesimally small concentrations.

As I stated in my keynote presentation at Joel Salatin’s Polyface farms last summer:

"The 'dose makes the poison' is an outdated concept. We need a new model that recognizes the potential for harm even at extremely low doses."

If methylene blue can alter biological systems at such minuscule doses, we must ask: What are the long-term consequences of introducing this synthetic chemical into the body?5

Documented Adverse Effects: Raising Red Flags

While proponents of methylene blue tout its benefits, there is no shortage of documented adverse effects in the medical literature, albeit at doses higher than the biohacking community typically takes. Some of the most concerning include:

Serotonin Syndrome

Multiple case reports have described patients developing serotonin syndrome after receiving methylene blue, particularly when combined with serotonergic psychiatric medications. Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition caused by excessive serotonin activity in the nervous system.6

Hemolytic Anemia

Methylene blue has been associated with hemolytic anemia, particularly in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. This potentially dangerous blood condition involves the premature destruction of red blood cells.7

Neurotoxicity

Multiple studies have documented neurotoxic effects of methylene blue, particularly at higher doses. A 2008 study in the journal Anesthesiology found that methylene blue had detrimental effects on the developing central nervous system in animal models.8

Cardiovascular Effects

Methylene blue can cause significant changes in blood pressure and heart rate. A review in the American Journal of Therapeutics noted:

"Methylene blue can cause severe hypertension when given in high doses, especially as an intravenous bolus. Other cardiovascular side effects include cardiac arrhythmias, coronary vasoconstriction, and decreased cardiac output."9

These documented effects are likely just the tip of the iceberg. Many adverse reactions may go unrecognized or unreported, especially more subtle long-term impacts. The full scope of methylene blue's effects on human health may not be apparent for decades.

Phycocyanin: A Natural Alternative to Methylene Blue

What is Phycocyanin?

Phycocyanin is a naturally occurring blue pigment-protein found in spirulina and cyanobacteria. It plays a vital role in photosynthesis and offers a powerful array of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective benefits—similar to those attributed to MB, but without the risks of synthetic interference associated with xenobiotic/petrochemically derived substances.

Spectral Overlap: Phycocyanin vs. Methylene Blue

Phycocyanin Absorption Peak: ~620-640 nm (overlapping with MB’s secondary peak at ~609 nm)

Phycocyanin Emission Peak: ~650-670 nm (close to MB’s primary peak at ~660-670 nm)

Shared Absorption Zone: ~610–650 nm—where both molecules are active.

This means that phycocyanin can serve the same purpose as MB in many therapeutic applications, including photodynamic therapy (PDT) and photobiomodulation, while avoiding MB’s synthetic toxicity.

Why Phycocyanin is Preferable to Methylene Blue

A Natural, Biocompatible Alternative

High Safety Profile

Millions of years of potential inclusion in the diet of the human species vs. only a few hundreds years for coal tar derivatives.

FDA-approved as a food colorant (E18 in the EU)

Oral LD50 (rats/mice): >5,000 mg/kg (suggesting very low toxicity)10

Comparatively, the Methylene Blue LD50: Oral ~1,180 mg/kg, IV ~44 mg/kg11

In other words, phycocyanin is over 4 times safer from the perspective of acute toxicity.

Conclusion: A Call for a Paradigm Shift

Methylene blue may have its place in emergency medicine, but its widespread use as a health supplement is problematic. The precautionary principle dictates that natural alternatives should be prioritized whenever possible.

Phycocyanin shares MB’s core benefits while avoiding its risks, making it a safer, natural alternative for those seeking enhanced mitochondrial function, cognitive support, and overall cellular health.

Here’s an example of an organic blue spirulina product high in phycocyanin that is affordable and easily available.

References

Caro, Heinrich. "Ueber die Einwirkung des Nitrobenzols auf aromatische Amine." Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 9, no. 1 (1876): 758–759. https://doi.org/10.1002/cber.187600901201.

Guttmann, Paul, and Paul Ehrlich. "Ueber die Wirkung des Methylenblau bei Malaria." Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift 28 (1891): 953–956. https://archive.org/details/berliner-klinische-wochenschrift-1891/page/953/mode/1up.

Quirk, Walter J. "Methylene Blue: An Old Drug with New Uses." Postgraduate Medicine 75, no. 4 (1984): 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.1984.11698730.

World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: 22nd List, 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2021.02.

Ji, Sayer. "The Methylene Blue Paradox: When a Synthetic Dye Becomes a Health Trend." GreenMedInfo, October 17, 2024. https://greenmedinfo.com/blog/methylene-blue-paradox-when-synthetic-dye-becomes-health-trend.

Barras, Héritier, Pierre B. Maeder, and Jean-Michel Gaspoz. "Methylene Blue and Serotonin Syndrome: A Word of Caution." Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 81, no. 2 (2010): 204. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.177329.

Liao, C. H., C. T. Lai, and C. C. Li. "Methylene Blue-Induced Hemolytic Anemia in a Patient with G6PD Deficiency: A Case Report." Veterinary and Human Toxicology 44, no. 1 (2002): 19–21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11824747/.

Vutskits, Laszlo, et al. "Adverse Effects of Methylene Blue on the Central Nervous System." Anesthesiology 108, no. 4 (2008): 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318167af15.

Clifton, Jack, II, and Joel B. Leikin. "Methylene Blue." American Journal of Therapeutics 10, no. 4 (2003): 289–291. https://doi.org/10.1097/00045391-200307000-00010.

Romay, Chantal, et al. "C-Phycocyanin: A Biliprotein with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Effects." Current Protein & Peptide Science 4, no. 3 (2003): 207–216. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389203033487216.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. "Methylene Blue." PubChem Compound Summary for CID 6099. Accessed March 9, 2025. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Methylene-blue.

Dr. Thomas Levy gave me personally a Spike detox protocol which I posted on my substack for everyone.. It was calling for 25mg of MD daily... It striked me from very begin because it is almost identical with Riboflavin's aromatic portion except for few atoms difference N instead of S in MB and the difference on colors blue(440-485)nm versus orange(590-625nm).. Riboflavin is known to be incredible ROS scavenger and the live giving properties, but since everyone was advertising MB, I just left it there. Not only that, Dr. Levy immediately responded with this link which tells way more details about how MB works:

https://www.tomlevymd.com/articles/omns20230204/Resolving-Colds-to-Advanced-COVID-with-Methylene-Blue

After seeing this now, I linked this post to that old post of mine to warn everyone, but possibly as always, the DOSE plays a role, here one doc from https://www.drlaurendeville.com/methylene-blue/:

"Methylene blue is a hormetic drug, which means that at low doses it can improve oxidative phosphorylation, enhance glucose uptake, oxygen utilization, ATP production, and decrease inflammation and oxidative stress. However, at higher doses, it can do the opposite of all of these things, converting from medicine to poison. Therefore, the dose matters greatly. I recommend making sure that you have a naturopathic or functional medicine provider’s help in the process."

becasue there are many health applications of that chenical indeed, here another summary:

https://www.drlamcoaching.com/blog/methylene-blue-as-a-photosensitizer/

So just in case, one need to search for detox of MB, for those who took too much, here some tips:

1. H2O2, which is good because it ALSO degrades graphene... :

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013935122021466

2. a bug, just not sure if it is genetically modified:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S092777652100391X

"Efficient degradation and detoxification of methylene blue dye by a newly isolated ligninolytic enzyme producing bacterium Bacillus albus MW407057"

and possibly many more.

The article that he references shows blue brains in people who had extremely high doses of MB for septic shock and severe hospitalizations, with post-mortems shortly after. They were also given other compounds that were not MB but were also included because of the colors of the brain after. The power of MB in the literature is undeniable with very little risk at low doses, less than 1mg/kg per day and orally given. I've used it for years in my patients with a massive amount of benefit, especially when it comes to improving mitochondrial function.